Gráinne Shaffrey

The shape of towns - Clones, Athy and Inistioge

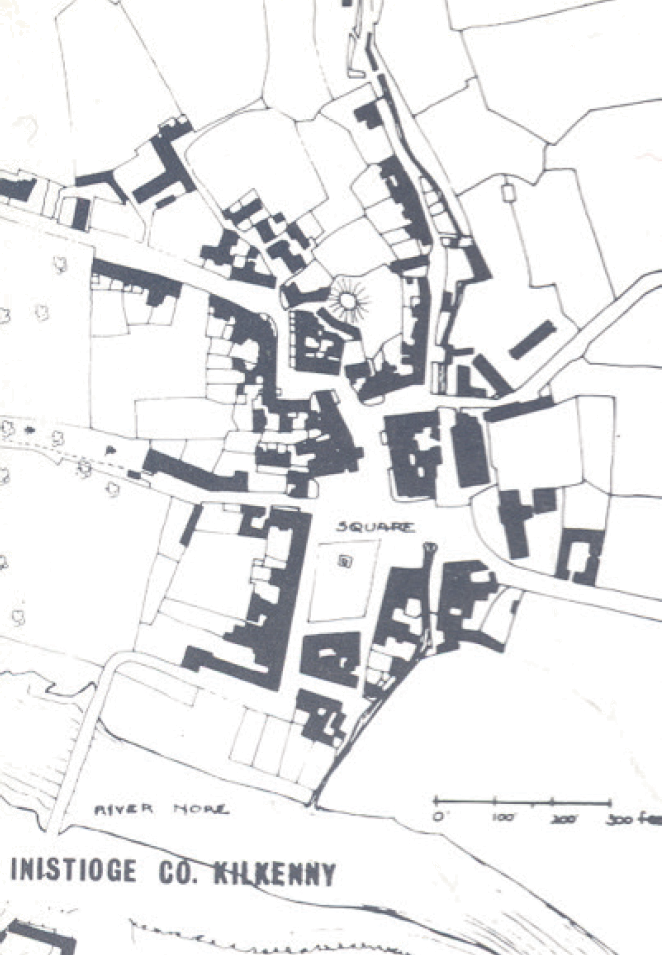

A village on a hill, to one side of the River Nore, Inistioge, Co. Kilkenny, provides clues as to how to make an urban settlement from mostly houses. Athy and Clones show a wealth of possibilities in making public spaces out of buildings. All are more than the buildings, all embrace their landscape, all have collective purpose, and all give a little more.

i) ”It’ll be a bitter day for this town if the world comes to an end.”

Home matters, place matters. Mrs. Canning – in the film version of Pat McCabe’s The Butcher Boy – speaks of her town, her home. Unnamed in book and film, the location is Clones, Co. Monaghan, and the tone and accent is all Clones.

Clones is a border town, a once significant commercial town, somewhat stranded atop a Drumlin. Architecturally, spatially, Clones is really rather wonderful. At its centre and along the high part of a gentle Drumlin hill, sloping, is the Diamond. A precious name for the main square of the town. A quintessential term used in the more northern parts of the island. The name places the place. The Diamond of Clones – a place of immense spatial qualities and continually inspiring. The ground plane is grass, concrete and asphalt. It has a noticeable incline – no level ground for easy pitching. Enclosed and formed by buildings almost exclusively three storeys high and yet varying in height by up to one floor. Buildings of civic, commercial and residential uses – of stone and painted plaster – frame the space and frame five views out to the surrounding landscape. Captured landscape expands and colours this public space. As with all Irish urban centres – at whatever scale – the view to the landscape and the sky are an intrinsic part of their urbanity.

“the view to the landscape and the sky are an intrinsic part of their urbanity”

Culture-Nature. While this green and pastoral vista charms and softens the pared-back classicism of the architecture (quintessential Irish urban vernacular), the intended focus, located at the high point of the Diamond, is the Catholic Church. All parts of this somewhat foreboding essay in dark limestone point upwards, no getting away from its dominance and its message. However, located immediately adjacent – under it’s elbow, as it were – is a short row of houses which confirm how well a home can sit within the middle of the primary civic space of the town. Enough front garden to create a threshold, yet not too much to disrupt the continuity of the architectural enclosure. Personal expression and care in these front areas, a generosity for the passer-by and the arts and crafts language tells of aspiration and time.

A Diamond of a space: cut, shaped and contained by buildings; relieved by openings extending out to embrace a related landscape and softened by grass and colour within.

ii) Una piazza, due chiesi

(A phrase encountered when studying the small towns of the hinterland of the Riviera di Ponente, each following a distinctive pattern. No matter how small, each had at least one square with two churches addressing it). Irish towns also possess recurring patterns and shapes, though Emily Square in Athy, Co. Kildare is unique. A Square in name, but in reality composed of five public spaces (‘squares’). Within an outer frame of three street edges and the broad River Barrow forming a fourth ‘edge’, are placed two civic buildings of contrasting architecture and function and, a tight urban block of high sophistication. The former Market House (now library and heritage centre) and the Courthouse (still in use), sit as object buildings with each facade addressing a sub-set of the Square. The inserted urban block acts as another ‘object’ placed into this square of fragments, and addresses the public spaces with typical, contiguous, urban streetscape. Within the body of this tight block are small spaces and open yards providing light, air and access – an essay in compact urban density and efficiency. And, softening it all, is the green informal riverbank with enduring traces of its former working edge still visible under the growth. The restraint of the enclosing architecture belies a complexity and generosity at the heart of Emily Square and all its multiple parts.

iii) A street made of houses, e due piazzi

Winding and sloping, from the entrance gates of Woodstock House, this street begins as detached houses (given edge and uniformity by the low boundary walls enclosing small front gardens), gradually pulls itself together as a joined up street as the end of the descent arrives, and culminates in a compact square which catches, holds and becalms the energy rolled down from the steep hill above. This square – Market Square – has two frames, an outer edge of buildings and an inner of trees, the tree crowns reaching above the built edge. This is a thermometer of a street, the mercury thread of the long street gathered in the bulb of the Square. And, looking back up from the Square, a glint of sun radiates from the pink-painted façade of a house part way up, enticing a return upwards to the warmth. Slipping the other way, along one side of the Square, a short neck of a street connects to the riverside, the street folding back with long buildings to create a working edge onto the River, at the bridge – now a public garden, a second civic square.